- Biblical Infallibility (and why we don’t need it).

- A Proper Christian Approach to Charity.

- Immigration and Ethnic issues; why Christianity isn’t necessarily pro-migrant or even pro-immigrant.

- Self-defense, violence and “just war” theory.

- A Christian attitude towards disasters and the anti-Christ(s).

- Christianity and Wealth.

- On Spirituality vs. Materiality.

I. On Biblical Infallibility

Many of us are receptive to radical traditionalist ideas. A central part of this theory is the idea of initiation. Initiation tends to happen as a chain, wherein a master initiates an apprentice. In doing so he passes on the “spiritual fire” and his connection to the spiritual center of the people. Without digressing too far from Christianity, this is an idea that exists internationally. Chinese for example (zhōng) means middle. Every great civilization views itself as being the center of its own universe. Western civilization and Christianity was no exception to this. When people concluded that the earth revolves around the sun and not vice-versa, this idea of spiritual centrality was threatened by material non-centrality. One does not need to follow the other.

Being the center of our own universe can be taken as a metaphysical or even a psychological statement; it does not need to be literal. If the earth revolves around the sun, that does not actually mean we cannot view ourselves as being the center of our own universe. If China (the middle kingdom) is apparently not located in the physical middle of the world, that doesn’t mean that the Chinese have no right to consider themselves as special. Similarly, the bible and Christians can view themselves as the center of the universe, or as important to themselves without needing to be physically and literally in the center of everything.

This brings us back to the subject of initiation and what it has to do with biblical infallibility. If you’ve ever tried to read the bible, you know that the Old Testament talks about who “begat” whom for many, many pages. As it turns out, all of that begetting was not a literal census of the old Hebrew and Jewish kingdoms. So why was it written down?

I would argue that the begetting was not meant to be a complete physical record of which men had which sons. It was an initiatory record. Each man, who himself had a connection to the spiritual center (in this case, to God) initiated his son or sons. The sons for whom this initiation worked were recorded as having been begotten. They would in turn try to pass on the spiritual “fire” to their sons and so-on. As long as a man had a child who could accept and be transformed by the initiation, they were recorded as begotten.

If one reads the bible in this way, the various material science flaws it arguably contains do not really matter. Indeed, people have known that there were historical errors in the Mikra (Old Testament) since before Christianity existed and it did not prevent people from trying to pass on their tradition to their children. The biblical tradition in particular passed from the Hebrews to the Jews, to Jesus and the early Christians (sometimes called Galileans), to the Romans, to the Europeans and eventually all over the world. The value of the bible is not necessarily in its supposed infallibility as a material record. Its real value lies in its function as a testament, one that can facilitate and maintain the spiritual middle among people who accept Christ.

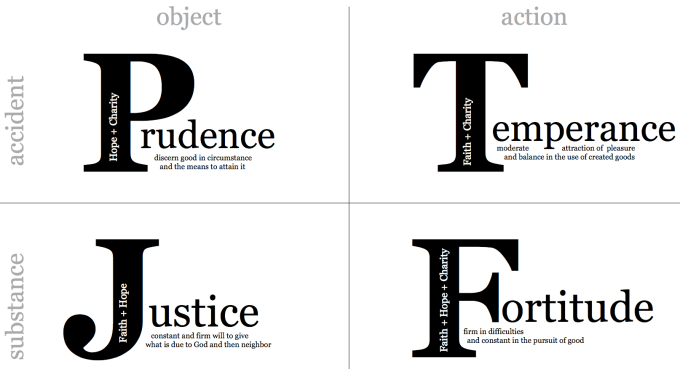

II. A Proper Christian Approach to Charity

Christianity is often used to try and guilt-trip or shame people who don’t support modern welfare policies. In my opinion, these policies are not authentically Christian.

A common line of attack refers to bible passages that shame those who are cruel to “the fatherless”. At the same time, the bible exalts fatherhood. It is not Christian to support policies that can discourage fatherhood. The “fatherless” in the bible is meant to refer to orphans of various types. It does not refer to the children of women who chose to be baby mommas; those women would have been stoned to death, exiled or pushed down into the equivalent of an untouchables caste for most of Christian history.

Similarly, throwing money at people unconditionally is not an accurate description of Christian values. The New Testament contains a few illustrations of this: the parable of the deserving and undeserving poor (read it if you haven’t), a statement that charity should be given freely and not coerced, a statement that real charity is anonymous and does not benefit the donor socially; none of those ideas mesh with modern welfare policies or virtue signaling.

III. On Immigration and those Muslim Migrants

There are passages in the bible that tell us to be kind to strangers. Does it follow from this that we have to accept all of those Muslim migrants into Europe? I don’t think it does.

Whenever someone in the bible gives a policy prescription, it almost always refers back to earlier policy prescriptions that were set down by the prophets. The early prophets said to be kind to a sojourner (a sojourner is a temporary traveler) provided that they follow your ways while in your land. Later comments about being kind to a stranger are arguably a reference to that earlier statement.

In the topical context of Muslim migrants, the bible would call us on to be kind to them provided that they 1. were going to be present temporarily (if one applies the sojourner term strictly) and 2. provided that they follow our ways, which in some cases would mean mean not acting like a Muslim. It is reaching to say that we need to provide for someone who intends to both stay permanently and not follow our ways, but instead they will follow their ways that are explicitly hostile to us. Unfortunately, people read passages out of context. Someone in the New Testament briefly talks about being kind to strangers and since the reader is ignorant of the earlier passages, they assume this means that the bible tells us to give hostile migrants a free ride. I don’t think that is a proper interpretation.

IV. On Self Defense, Violence and “Just War” Theory.

This is potentially a long subject. I’ll begin by stating that all of those Christian warriors and knights from the past were not completely wrong about their own religion; they often studied it far more than modern, pacifist-leaning Christians have. There are multiple instances of violence or sanction of violence coming from Jesus.

First, Jesus told his followers to acquire swords when they were traveling into Jerusalem. He said that a man with a sword in his house makes his house safe. This shows that a Christian can defend themselves and their home from physical violence, bandits, robbery etc.

Second, a Christian is expected to turn the other cheek over things like insults to pride or procedural troubles in regards to himself. This is not the same thing as being a pacifist. It is pacifism in very limited contexts. A Christian can, for example, flee from persecution; you aren’t obligated to make yourself into a punching bag. It is also arguably possible for a Christian to defend other people from these things that he would not defend himself from. This is where the idea of the “Christian Avenger” comes from; when you defend each other from these things you can promote and protect your community without making it explicitly and materially about yourself.

Third, people have argued that if you know your enemy is plotting something and the best defense is a good offense, you can attack. Very influential Christians like St. Augustine and many Popes have agreed with this theory. Obviously it is a very contentious issue because of the potential for abuse but it is historically not a minority position.

In sum, Christianity is not a pacifist religion. It’s a religion with pacifist elements individually but not necessarily communally.

V. A Christian Attitude Towards Disasters and the Anti-Christ(s).

Early Christians (and those of other religious persuasions) believed that natural disasters meant that God was angry with them for being sinners. Now we know that most natural disasters can be explicitly linked to gradually growing weather phenomenon. They seemingly have nothing to do with the number of sinners present in an area. Are we better now that we know this?

Sociologically, let’s consider the implications of these ideas. When people believed that a storm or an earthquake meant that God was mad at them for being sinners, their reaction to a disaster in some cases would be to behave better. The community would band together. Today, a natural disaster has no meaning and therefore it is often seen as an excuse to loot, rape, burn and kill. Certainly it might be “ignorant” to say that an earthquake signifies God’s anger at sinners. Ironically, the “ignorant” position was actually better for the community than the factually correct position.

Pandora’s box is already open on this issue but when you read a passage in the bible that blames something apparently arbitrary on sinners, keep this is mind: it was probably a very smart thing to blame it on the sinners.

Similarly, the anti-Christ has been declared to have come many times. And yet the world keeps on going. If one steps back, they might notice that the description of the anti-Christ depicts a common type of demagogue. If we are presuming that these demagogues should be opposed, viewing one of them as the anti-Christ would probably be a very effective method for trying to oppose them. Was Napoleon the anti-Christ? Is Obama the anti-Christ? According to a strict reading, no, they couldn’t be because we are still here. But we could consider such people to be anti-Christs, plural.

VI. On Christianity and Wealth.

Christianity is hostile to wealth but there is some room for interpretation here. A good example of this is how the bible describes Kings that God was pleased with. Few people, perhaps no one, is richer than a King. That means the King was rich but entered into haven. How are we to reconcile this?

This is only my own theory, but the Greek word for wealth (sometimes romanized as “plousis”) can also mean “material abundance” and not just “rich”. According to this reading, a person who lives humbly might possess great assets and/or power, but so long as he doesn’t live with and for material abundance, he might still be pleasing to God.

VII. On Spirituality vs. Materiality.

One of the underlying points I want to present here is that a distinction exists between spiritual concepts, which necessarily will be described with material words, and with material concepts. This is more obvious if someone has studied Old Greek in the context of the bible and I will give another example now.

When a Christian is told to “love their enemies” that might sound like a pacifist statement. It might sound like it conflicts with other things in the bible. It does not conflict as much if someone understands that Greek has many words for love. The Greek word for love used in the passage on “loving” one’s enemies can arguably mean “to esteem someone highly, relative to others”. According to this reading, loving your enemy does not mean being a pacifist. It could also mean to respect your enemies, to treat them with honor, perhaps to try and teach them. This is much more nuanced than simply “loving” them in the English sense of the word.

Similarly, Christianity tells people to forgive. It also says to treat people you can’t reconcile with as tax or toll collectors. Forgiveness does not necessarily mean letting someone have their way, or giving them license to do anything they want. Forgiveness can be a purely spiritual thing. You might forgive someone for committing some crime, that is to say you would not pass judgment upon their soul, but you would still apply the punishment suitable for that crime to them. In this sense then, you can theoretically forgive someone you are obligated to do something bad to, up to and including killing them. The underlying theory is that you don’t hold onto malice yourself. External behavior can be illustrative of what someone feels on the inside but it is not the only thing that matters. It isn’t strictly determinative.

Conclusion

For me, it took a long time before I felt like I understood the bible. I’ve also read some of the Christian apocrypha, which sometimes takes the bible in a more radical traditionalist direction, such as the gospel of Judas. Those things aren’t canon however and so I won’t discuss them in any more detail right now. What I will write is that I had an epiphany one day which made the bible easy to understand, at least for me.

The realization I had is that in modern life, we are constantly told that we can only love someone or only hate someone. If you side with this camp or that camp, you are loving or you are hating. No nuance is allowed. This isn’t how the human mind really works. It’s actually normal (and sane) to both love and hate people at the same time. So if you read the bible again at some time in the future, the most important thing I can advise you on is this: remember that the authors presumed you could love and hate someone at the same time. So when you read about a person in the bible saying they love this person, or that person, or all of humanity, and then they start fighting someone and talking about how much they hate them, you don’t have to view it as a contradiction. Maybe they really do love parts of that person, or love that person, but they also hate parts of them or hate what the person is doing. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that, I think it’s a normal way for someone to be. It’s far stranger to pretend that because you voted for Obama you now love all minorities and will give them other people’s money, but if you voted for Romney you must hate them and want them all to die. Maybe we love some of them and hate others of them, or far more likely we might love things about “them” in general but hate other things about them. There’s nothing wrong with that. Don’t get funneled into the false dichotomies and shallow dialectics that people use to try and manipulate you into thinking what they want you to think.